Fire Catastrophes and Meteorology

Published:

Last month the NFPA released several reports on fire losses in 2012. The report Catastrophic Multi-death Fires in 2012 covers the seventeen incidents that had five or more deaths. These incidents make up .001% of the total fires for the year and 2.9% of the total deaths.

The incident with the single largest loss-of-life was not any of the usual suspects such as a building collapse or a gas explosion. It was a series of car accidents due to low visibility from a brush fire near a highway. On January 29th, on Interstate 75 near Gainesville, Florida, 25 vehicles were involved in six crashes that left 11 people dead. The helicopter footage of the aftermath is harrowing but tenable given the visibility captured in the photograph (via Daily Mail UK).

The timeline of that day’s events as fascinating as it is tragic:

- 1435 hours, January 28th - Brush starts, agencies notified

- 1737 - DOT places Fog/Smoke signs on US 441

- 2003 - Fire Service (FS) officer contacts High Patrol (HP) officer, informs HP that FS is leaving the scene, makes sure HP will continue to monitor. FS states, "We don’t know what it’s gonna do, weather wise, so that thing is pretty close to 441 and 75 and we don’t want any major accidents."

- 2028 - HP officer returns to fire scene, reports that fire is out with no smoke. Incident considered closed.

- 2331 - HP notified of six vehicle crash but not of low visibility.

- 2354 - HP notified of accident with semi-truck and two vehicles due to smoke.

- 0010, January 29th - Interstate 75 is shutdown to traffic

- 0326 - interstate 75 reopens

- 0350 - DOT maintenance drives 75, find S is clear and N is solid smoke

- 0401 - HP receives calls of multiple accidents.

- 0409 - Interstate 75 permanently shutdown.

The Law Enforcement Incident Review highlights many factors that went wrong here, but I was struck by the meteorological dimension. The sudden drop in visibility was due to a phenomenon called inversion where a shift in the atmosphere’s temperature layers traps smoke. After a similar situation in Florida in 2008 led to a 70 vehicle accident with 4 deaths, the highway patrol updated a checklist for smoke/fog incidents which now included checking the Low Visibility Occurrence Risk Index and getting a spot forecast from the National Weather Service. In 2012, neither of these things were done.

The Interstate 75 catastrophe is neither the worse nor the most recent fire tragedy where the weather played an important role. Just four months ago, in what was the deadliest event for firefighters since the 9-11 attacks, 19 firefighters were lost in the summer wildfires in Yarnell Arizona when the winds changed. My former Cornell bandmate Owen Shieh, now the Weather and Climate Program Coordinator at the National Disaster Preparedness Center, posted an very detailed analysis of what happened and how it could have been avoided, and concludes with the crucial question for emergency decision-making - What else can be done to bridge the gap between the science and the decisions?

Unfortunately, it is not clear whether agencies in Florida are taking the weather more seriously. A year after the Interstate 75 incident, the Florida DOT, Forest Service, and Highway Patrol have reportedly collaborated to make improvements in terms of inter-department communications, cameras to monitor the highway, signage to warn drivers, sensors to monitor traffic speeds, and increased training for responded to fog related accidents.

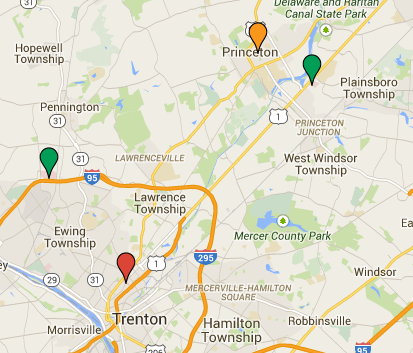

Map of past and current hospitals in the Princeton area.

Map of past and current hospitals in the Princeton area. University Medical Center of Princeton at Plainsboro: curved for your health

University Medical Center of Princeton at Plainsboro: curved for your health