I am obsessed with this clever National Night video that went viral a year ago that encouraged Singaporeans to buy Mentos and increase Singapore’s birth rate.

The award-winning ad campaign picked up on Singapore’s national concerns about having the lowest fertility rate in the world. The government’s recent response has been economic incentives called Baby Bonuses. With these economic incentives the government has come full circle from its 1970 campaign “Stop At Two” which ended tax deductions and maternity leave for having a third child due to Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew’s fears of overcrowding and economic burdens. As shown below, the birthrate fell drastically in the mid 70’s, which led to a new fear - a shrinking tax base. The government officially reversed “Stop At Two” in 1986 with the timid slogan “Have Three or More (if you can afford it)” and have been periodically increasing incentives since.

[caption id=”attachment_149” align=”aligncenter” width=”480”] Data from http://www.singstat.gov.sg[/caption]

Data from http://www.singstat.gov.sg[/caption]

So have the government policies or the smooth National Day R&B had an effect? It doesn’t look like it looking at the monthly birth rate data below. There are no obvious baby bumps nine months after augmentations to the government incentives were announced or nine months after last National Day as denoted by the green and red lines.

[caption id=”attachment_151” align=”aligncenter” width=”480”] Data from http://www.ica.gov.sg/page.aspx?pageid=369 and http://data.un.org/Data.aspx?d=POP&f=tableCode:55[/caption]

Data from http://www.ica.gov.sg/page.aspx?pageid=369 and http://data.un.org/Data.aspx?d=POP&f=tableCode:55[/caption]

It may be no surprise that linear regressions with month controls and baby bonus indicators or with month and year controls find no effect for the viral video, but the government policies also show no effect looking across a number of time spans. There are monthly variations, but what seemed unusual were statistically significant effects of about a 5% increase for 2012 and decrease for 2010. These match up with the Chinese zodiac years of the Dragon and the Tiger, may correlate with higher and lower birthrates respectively (Chua 2009). Indeed, the effects become more pronounced when moving January to the year before to better represent the Chinese calendar.

The government must see that the incentives have not had the desired effect and keeps changing the size of bonuses and the types of perks that new parents can get. In January the government announced the Marriage & Parenthood Package 2013, which again increases the monetary incentives but includes more alternative benefits such as priority housing, child care leave and paternity leave.

As for Mentos, their 2013 National Day video is not as catchy, but it is interesting in that the national concern they focus on is year is over-crowding. It seems that Singapore’s problem is not that there are not enough people; it is that there are not enough young people. That is why Singapore has also changed its immigration policy. Non-residents made up 10% of the population in 1990 and over 25% in 2010, which has created social tensions. Indeed, there is no easy solution to what now-retired Lee Kuan Yew calls the biggest long-term threat to Singapore, who is counting on future leaders to find a solution. Unfortunately the next Year of the Dragon is not for another 11 years.

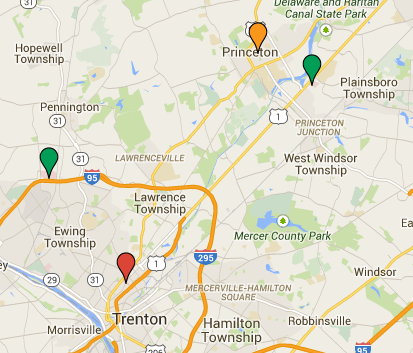

Map of past and current hospitals in the Princeton area.

Map of past and current hospitals in the Princeton area. University Medical Center of Princeton at Plainsboro: curved for your health

University Medical Center of Princeton at Plainsboro: curved for your health